It is well-known that accurate modelling is particularly important in project finance transactions. But why is this? One can think of this in terms of the likelihood and benefits/costs of getting these calculations right or wrong. Models are at their most useful when the chance of being wrong is relatively low, but the cost of being wrong is relatively high.

In most project finance transactions cash flows are relatively predictable and the likelihood of the model resembling reality is therefore pretty high; likewise where these assets are highly leveraged, the cost of a mistake can be very substantial (and could indeed wipe out much of the value of the remaining equity in the project). Where cash flows are more volatile, as in many other areas of corporate finance, it is often not practical to use a similarly detailed model to try to give the same degree of confidence in the outputs; whether due to natural variation or human error, reality simply will not match the initial projections. A detailed and accurate model is therefore a fundamental requirement to support the high levels of gearing that we are accustomed to seeing in project finance.

In terms of the ‘at-risk’ areas of your model, these depend on the nature of the assets and the details of the transaction. For instance, an LLCR calculation might be riddled with errors, but if this is not a ratio that is covered in your financing documents (as is increasingly common in renewables transactions) then the cost of getting this wrong is virtually nil. But there are some standard hot-spots for errors across sectors that modellers should always be aware of:

- Inflation – errors here are both pretty common and often fairly expensive, as any mistake will compound over time. Small changes to base dates or the application of inflation rates will make a big difference to your cash flows at the back end of the debt profile. A further alarm bell should be set off if the model’s cost/price for the current year or period fails to match what is actually paid/received (it sounds obvious but is routinely wrong)

- Documents – these are written by lawyers who are not necessarily renowned for their modelling ability, whilst the task of carefully reading the documents is routinely given to a different team member to the one doing the modelling. That this gives rise to errors should surprise no-one. There are often subtle points around the timing of cash flows or the calculation of cover ratios (to give two examples) that can get missed. Crucially if such a problem is unearthed at a later stage, the legal document will always take precedence over whatever was modelled, thereby making the subsequent rectification of the problem much harder.

- Financial close funds flow – in general, models are built around approximations over time periods that are measured in months or years. This is perfectly reasonable and sensible – except at (or soon after) financial close. Large amounts of money move between parties and both the amounts and the process (something on which a model is normally silent) need to be carefully considered. A funds flow statement needs to capture all relevant cash flows and the practicalities of any transfers as it is not possible to take a hand-wavy approach of saying ‘cash flow x nets off against cash flow y’. Understandably any problems here tend to come out of the woodwork pretty quickly when an advisor or exiting lender does not get paid everything they expected to get paid.

What are the lessons here? That depends a bit on whether you are a modeller or looking for someone to do your modelling. But a few things hold either way:

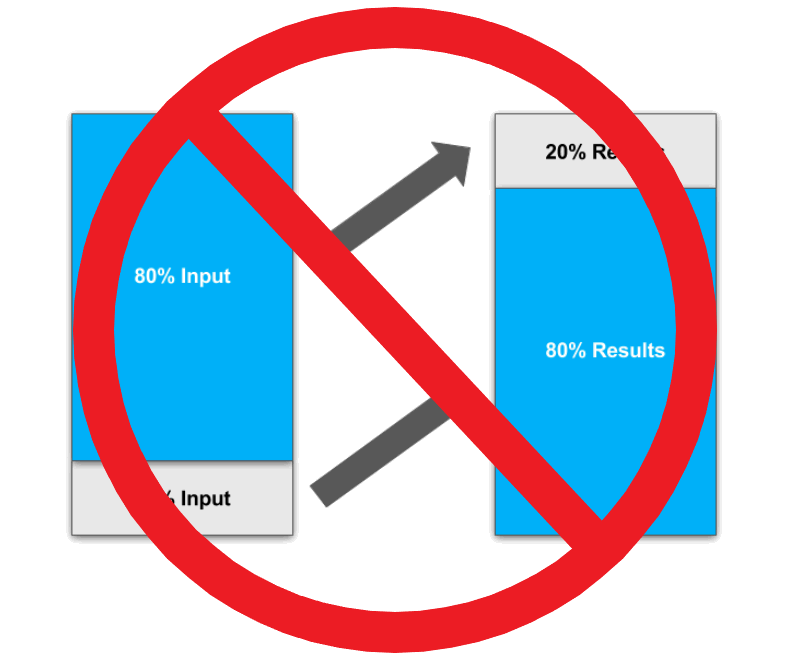

- The 80/20 rule does not really apply – the famous rule of thumb of ‘putting in 20% of the effort to get 80% of the way there’ is inappropriate in project finance. You might be able to get much of the way to the right answer but the details of a project finance transaction really do matter and a high-level sense check of the outputs will not always get this right. Modellers should go through the credit agreements and key project documents in forensic detail – division of labour is not a helpful principle here. Take your transaction modelling seriously and it will repay whatever investment is required to make that happen whether that is time, effort, or your finest British pounds (other currencies are available).

- You need multiple sense checks – the best models contain multiple audit checks that between them cover off every key output. Whilst including these is best practice, it does not fully immunise the model from either logical errors (something can always slip through the net no matter how tight the mesh of audit checks) or commercial errors. It helps to have a fresh pair of eyes looking at things (at least) before an initial model goes out and each time there are substantial changes. More generally, it is a good sign if more time is spent checking a model than building it.

- A modeller should understand the broader transaction – a model is not just an illustration of a transaction that can be bolted on to the main body of activity. If the model (and indeed its author) is kept at arms’ length then it is very easy to lose track of the real drivers of value in a transaction. Financial decisions depend on quantitative analysis and the quality of those decisions will be very strongly correlated with the quality of information that is provided to decision makers; the transaction model informs these decisions more than any other single document or tool. You should negotiate the model rather than model the negotiations – and this means that everyone should understand the key outputs of the model.

As an advisor, Elgar Middleton has always considered the financial model to be central to our advisory services. The modeller is fully integrated into the team advising the client from day 1 and their role includes reviewing all the term-sheets, iterations of the finance documents and providing constructive feedback to the legal advisors to ensure documents and models align. Unsurprisingly this means that the modeller is not a junior member of the team and in some cases the work is undertaken by one of the partners. Even so, every model is subject to repeated peer reviews at various stages throughout each transaction, because even the smallest of slips can have the largest of consequences.